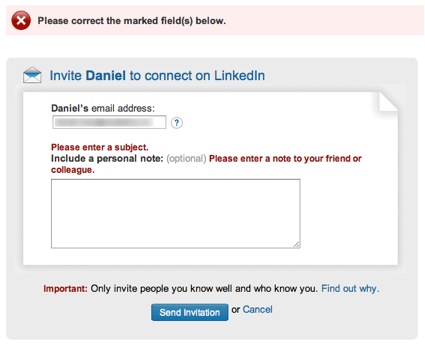

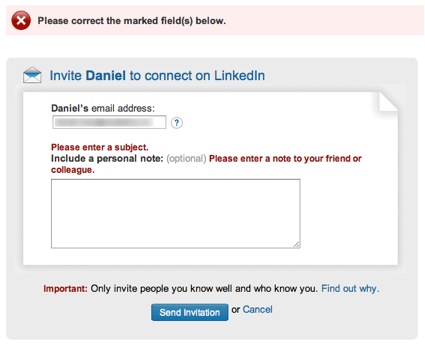

When was the last time you used an application that was just impossible to comprehend?

<!–more–>

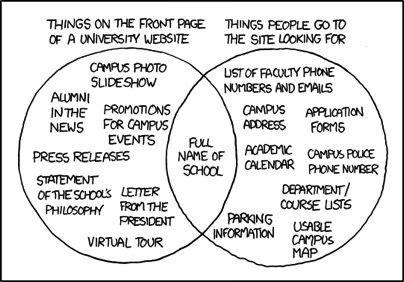

Or that you visited a web page that made it hard to find what you were looking for?

I’m guessing you don’t have to rack your brain too hard to come up with an example. In fact, if you’re reading this at work, you might very well have opened our newsletter just to take a break from the confusing enterprise software you’re stuck using for your job.

The Science Behind the Suck

During World War II, Army Air Force scientists noticed that changes in cockpit design often had disastrous effects on pilot performance. When the mental and physical capabilities of pilots did not align with the design of the aircraft, pilots were much more likely to make a mistake. Considering these “human factors” as part of the design turned out to be an important safety and performance issue. This insight led to a new science that linked human psychology to product design.

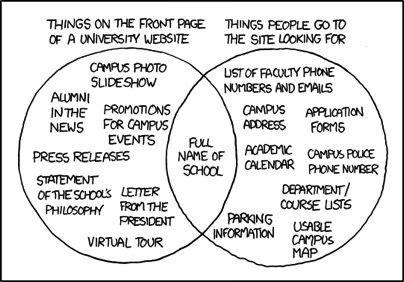

Fast forward to 1990s. Computer software starts to become mainstream. No longer the realm of the most technical users, human capabilities and product design started to clash again. Building on what the Human Factors researchers had learned, the science of usability engineering took off to meet the challenges of software design.

Some of the important human characteristics that must be considered include:

- People have limited working memory capacities

- Attention limits the ability of our minds to process only so many thoughts and inputs at once

- Our eyes are drawn to salient features

- We mentally group things in predictable ways

- Our perceptions are colored by our experience and expectations

So how do you use this knowledge to make digital products that don’t give people fits? I’ll give you a hint: you’ll have to do a little more than add a line that “the application will be designed with usability in mind” to your requirements doc.

User-centered design is an approach to designing and developing software that results in applications and websites that are easier to use and better meet the needs of users.

What Is User-Centered Design

It starts by putting users at the forefront of design decision making. That’s what user-centered design is all about. Through research, observation, iterative design, and usability testing, we can understand the needs and behaviors of our users and use our expertise as designers to craft products which are useful, usable, and pleasurable to the users.

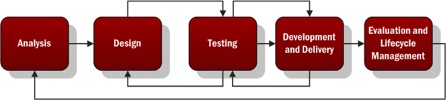

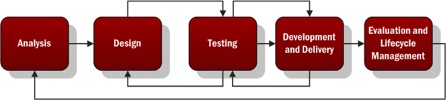

A typical user-centered design process would go something like this:

- Analysis – Identify the characteristics of the users, user goals, context of use, and business goals. Talk to actual users and business stakeholders.

- Design – Create mockups or lo-fi, low cost prototypes of the solution based on the information gathered in the analysis phase.

- Testing – Test your mockups or prototypes with actual users to determine what works and what needs to be improved. Iterate on the design and testing phases to improve the process and move closer to …

- Development and Delivery – Building as you iterate through the test and design phase, you’ll approach higher fidelity until you’re ready to complete the development and delivery of your project.

- Evaluation and Lifecycle Management – Evaluate the success of the project against the characteristics defined in step 1 by measuring the behavior of actual users. Continue to ensure the product is updated using user-centered principles throughout the lifecycle.

Noticing a theme?

Why Is That So Important?

In the realm of ecommerce, the consultants User Interface Engineering used user testing to discover a usability flaw that was costing a major retailer $300M in lost revenue (http://www.uie.com/articles/three_hund_million_button/). When designing products, Jakob Nielsen estimates that spending 10% of a project’s budget on usability doubles the quality metrics for the project (http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/).

When designing intranets and enterprise applications for internal use, your users may not have somewhere else to turn. In those cases, you don’t have to worry about losing customers. But poorly designed applications can cause all sorts of problems.

- Employees are less efficient at their jobs when the tools they need are hard to use.

- Confusing interfaces may cause employees to make costly errors.

- Users blame themselves when they have trouble using an application, so having to spend the day using a suite of poorly designed applications leads to unhappy workers and lowered employee morale.

But We Don’t Have Designers! How Can I Get Me Some Of That User-Centered Design?

While you may not have designers, someone does design every application. It may be a business analyst or product manager doing mockups in Visio or it might be the developer turning user stories directly into front-end code. Inadvertent design is still design.

You don’t have to bring in an expensive agency or hire a team of User Experience Designers when you’re just starting out. The best way to improve the user experience of your products is simply to watch your users use your product.

User Interface Engineering has a list of excellent ways to start your user research (http://www.uie.com/articles/starting_user_research/).

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more, I suggest starting with the following books:

- Don’t Make Me Think by Steve Krug – The classic introduction to designing websites and applications for usability. Quick and easy to read, it’s a must read for anybody involved in product work.

- The Design of Everyday Things by Donald Norman – Norman is a pre-eminent cognitive psychologist and designer. Norman goes more in depth into the psychology of design than Krug, but this book is still quite accessible.