If, after examining and analyzing a problem, I find the best solution, I recommend and, at times, fight for that solution. This approach seems so self-evidently correct that I’m shocked to find myself even writing it.

Tag: design

As technical writing consultants, our job is to advise and recommend. Of course, that advice and those recommendations cover lots of different aspects of the entire process. Obviously, we review the material and try to organize the information so we can present it in the most effective, most efficient way possible. Rarely, if ever, do we receive much push-back from our clients on this part of the process. After all, that’s why they hired us.

And while writing and organizing content remains one of the more important parts of our work, we also believe that we have some insight into what tools to use make that efficient presentation of material possible. Unfortunately, our clients don’t always agree.

Here are some examples.

A company approached us with a problem. It produced a piece of hardware that it sold with optional modules. The company wanted to ship a manual that covered only the modules that were purchased, not all of the modules offered. The problem the company was having was that it had created the manual in Word and either it had to manually manipulate the document each time it made a sale – delete the sections for the modules that weren’t purchased and renumber the chapters and pagination – or send a manual with all of the features and text for all of the modules. Which always creates problems – “Why can’t I get this machine to do what it shows in Chapter 8?” Answer: “Because you didn’t buy the module described in Chapter 8!”

We suggested we import the contents of their manual into FrameMaker and use FrameMaker’s conditional text feature to mark the text that belongs to each module. In this way, we could mark whole chapters that related to individual modules, as well as words and paragraphs – in feature lists, for example, in the introductory sections of the manual – so the resulting document would reflect only those modules that were purchased. A brilliant solution, we thought, and so did the client. Happy client; happy consultant.

A different company talked to us about documenting a large enterprise software package that also offered different, optional modules. After discussing the application with the SMEs and reviewing the existing documentation (our due diligence), we concluded that the final document would be very large – it was a VERY large enterprise software application that did many things – with lots of graphics and screen shots and would not do well in Word. Furthermore, the client admitted that its clients didn’t always buy all of the modules and so would want the ability to offer a manual that only included the modules purchased.

Fresh off the previous consulting engagement in which we were able to address the hardware manufacturer’s similar problem, we proposed using FrameMaker and marking the sections describing each module as conditional text. Then, the company could produce a “customized” document for each of its sales. Not only would we solve the “purchased module” problem, we argued, but we could assure the client that FrameMaker would handle the large size of the document much better than Word because that was what FrameMaker was designed to do and Word was not.

Our contact at the company agreed with us but found little support with her management. Why? Management wanted to be sure it could revise the document without having to hire a FrameMaker “expert” and so wanted it done in Word. What about the optional module problem? “We’ll deal with it internally,” they said. Since in our line of work, the customer is always right, we wrote the manual in Word and regretted every minute we spent on it, knowing the resulting material was inadequate. Alas.

I’ve yet to hear of someone instructing a plumber as to what kind of wrench to use to fix a leaking faucet or tell a carpenter what type of blade to use to cut a piece of wood, or, as I’ve said before, told a developer what language to use to code an application. We hire experts and rely on them to advise and recommend the best way to solve a problem. Technical writers are the experts. Listen to their recommendations.

Recently, a prospect called us about a training guide he needed written for a new enterprise application his company had recently purchased and was trying to implement. Unfortunately, he had already paid the company that developed the application to create training materials but found, once he had a chance to review the materials, that they were not only impenetrable and useless from a user’s point of view but mostly incorrect as well. A complete waste of money. Alas.

Objectivity tends to be one of the core values of technical fields. The fundamental laws of physics dictate the properties of microprocessors, and chemistry defines the properties of the materials we use. These methods make up the API, determining how that application behaves and what it is capable of doing. The way that people interact with technology, however, is anything but objective. They bring a lifetime’s worth of experiences that guide their behavior and frame their expectations for both what the technology will do for them and how it will perform its duty.

The user interface of an application – even one with a convoluted design – gives users some sense about how to navigate the application. It may be painful, but users can usually muddle through if they have to. APIs, on the other hand, offer no natural affordances or signifiers allowing developers to learn how to use the API. Therefore, good documentation is crucial for any API project.

Eric Sedor is a senior software engineer at MongoLab, a cloud-based database provider located in San Francisco, and frequent contributor to The Technical Reader. Eric cut his technical writing teeth at Shoap Technical Services before returning to his true passion, software engineering.

From touch screens of various sizes, to Microsoft Kinect™, Google Glass, Fitbit, and Square, we’re seeing a panoply of new devices that broaden both what technology can do and how we interact with it. This explosion of new interaction technologies has even created a bit of a hiring frenzy for interaction, user experience designers, and human computer interaction specialists whose job it is to design how exactly we are going to get all these new toys to do what they are supposed to. Dreaming up fantastic new ways to interact with all this fancy technology is one thing, but how do those dreams become applications, and how do people know how to use them once they get them?

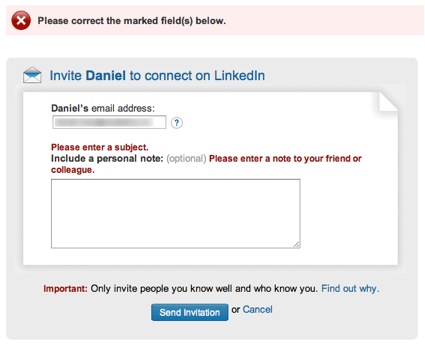

When was the last time you used an application that was just impossible to comprehend?

<!–more–>

Or that you visited a web page that made it hard to find what you were looking for?

I’m guessing you don’t have to rack your brain too hard to come up with an example. In fact, if you’re reading this at work, you might very well have opened our newsletter just to take a break from the confusing enterprise software you’re stuck using for your job.

The Science Behind the Suck

During World War II, Army Air Force scientists noticed that changes in cockpit design often had disastrous effects on pilot performance. When the mental and physical capabilities of pilots did not align with the design of the aircraft, pilots were much more likely to make a mistake. Considering these “human factors” as part of the design turned out to be an important safety and performance issue. This insight led to a new science that linked human psychology to product design.

Fast forward to 1990s. Computer software starts to become mainstream. No longer the realm of the most technical users, human capabilities and product design started to clash again. Building on what the Human Factors researchers had learned, the science of usability engineering took off to meet the challenges of software design.

Some of the important human characteristics that must be considered include:

- People have limited working memory capacities

- Attention limits the ability of our minds to process only so many thoughts and inputs at once

- Our eyes are drawn to salient features

- We mentally group things in predictable ways

- Our perceptions are colored by our experience and expectations

So how do you use this knowledge to make digital products that don’t give people fits? I’ll give you a hint: you’ll have to do a little more than add a line that “the application will be designed with usability in mind” to your requirements doc.

User-centered design is an approach to designing and developing software that results in applications and websites that are easier to use and better meet the needs of users.

What Is User-Centered Design

It starts by putting users at the forefront of design decision making. That’s what user-centered design is all about. Through research, observation, iterative design, and usability testing, we can understand the needs and behaviors of our users and use our expertise as designers to craft products which are useful, usable, and pleasurable to the users.

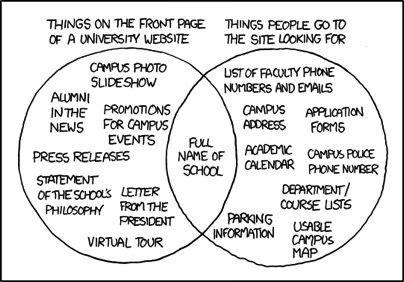

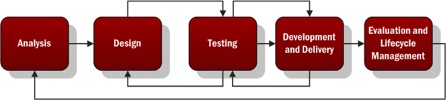

A typical user-centered design process would go something like this:

- Analysis – Identify the characteristics of the users, user goals, context of use, and business goals. Talk to actual users and business stakeholders.

- Design – Create mockups or lo-fi, low cost prototypes of the solution based on the information gathered in the analysis phase.

- Testing – Test your mockups or prototypes with actual users to determine what works and what needs to be improved. Iterate on the design and testing phases to improve the process and move closer to …

- Development and Delivery – Building as you iterate through the test and design phase, you’ll approach higher fidelity until you’re ready to complete the development and delivery of your project.

- Evaluation and Lifecycle Management – Evaluate the success of the project against the characteristics defined in step 1 by measuring the behavior of actual users. Continue to ensure the product is updated using user-centered principles throughout the lifecycle.

Noticing a theme?

Why Is That So Important?

In the realm of ecommerce, the consultants User Interface Engineering used user testing to discover a usability flaw that was costing a major retailer $300M in lost revenue (http://www.uie.com/articles/three_hund_million_button/). When designing products, Jakob Nielsen estimates that spending 10% of a project’s budget on usability doubles the quality metrics for the project (http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/).

When designing intranets and enterprise applications for internal use, your users may not have somewhere else to turn. In those cases, you don’t have to worry about losing customers. But poorly designed applications can cause all sorts of problems.

- Employees are less efficient at their jobs when the tools they need are hard to use.

- Confusing interfaces may cause employees to make costly errors.

- Users blame themselves when they have trouble using an application, so having to spend the day using a suite of poorly designed applications leads to unhappy workers and lowered employee morale.

But We Don’t Have Designers! How Can I Get Me Some Of That User-Centered Design?

While you may not have designers, someone does design every application. It may be a business analyst or product manager doing mockups in Visio or it might be the developer turning user stories directly into front-end code. Inadvertent design is still design.

You don’t have to bring in an expensive agency or hire a team of User Experience Designers when you’re just starting out. The best way to improve the user experience of your products is simply to watch your users use your product.

User Interface Engineering has a list of excellent ways to start your user research (http://www.uie.com/articles/starting_user_research/).

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more, I suggest starting with the following books:

- Don’t Make Me Think by Steve Krug – The classic introduction to designing websites and applications for usability. Quick and easy to read, it’s a must read for anybody involved in product work.

- The Design of Everyday Things by Donald Norman – Norman is a pre-eminent cognitive psychologist and designer. Norman goes more in depth into the psychology of design than Krug, but this book is still quite accessible.

Without sequencing tasks to a specific purpose, the commonplace actions that constitute office work make little sense and no one would sit around all day doing them, ever. We all recognize the need for processes, but that’s generally where agreement ends.

For additional information regarding Waterfall/Agile development and how it impacts technical writing, please refer to previous blog posts written by Eric Sedor and Shaun Kelly.

Moving a product out the door to capitalize on market demand is a necessity – it’s simple economics! Consumers demand constant product improvements. This “out with the old, in with the new” mentality has led many successful companies to switch from Waterfall development to Agile. What does this mean exactly? For the uninitiated, use this simple analogy. Waterfall development can be compared to a marathon. All software features are built in one long process and then errors are fixed. Agile development is more like a series of sprints. Software is released in a series of small iterations. Each release includes a few added features, and errors are corrected along the way rather than at the end. As you can imagine, the switch to Agile development completely shatters the status quo and roles of people associated with the development teams. This led us to wonder: Specifically, how does the switch to Agile impact the role of technical writers?